Of the seven installments in this series, this one is the most difficult to write (and hopefully the most difficult to read).

Before continuing, I’d like to propose a difference between “identity” and “race.” Many people emphasize one aspect or another of their physical and emotional makeup as an identity. Some people identify as conservative, others as liberal; some as hard-core show-me-the-data wonks and others as earthy, feel-good life coaches. Identities are positive, they are an expression of self, not an expression of someone else.

In contrast, race has degenerated into something of difference, something discriminating, differentiating, and prejudicial. Joe is white, so he must be guilty of slavery, colonialism, and favoritism. Malcolm is black, so he must be poor, disenfranchised, and a victim.

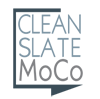

I recognized this distinction (which may or may not be justified) quite some time ago, and it fully crystallized after reading My Seven Black Fathers.

In his autobiography, Will Jawando places a huge emphasis on his identity as an African American (p. 125):

As a Black boy, I needed my Black fathers—as this book testifies to on nearly every page.

That’s positive. That’s a declaration of identity. It’s a realization of who he is and whom he needs. How much better we would all be if we could come to that realization, instead of pursuing nonsense such as likes on social media.

Jawando also evokes race, particularly anti-white race. He describes an altercation at school (p. 40):

Had a white kid bumped into a classmate on the playground, it would have been an accident. And there would have been no shame in asking to use the bathroom. A white kid wouldn’t have had to squint at the board from the back of the room. Had I been a white boy, I would have been appreciated for being outgoing and forthright, smart, a go-getter. Instead, where I was concerned, white teachers and administrators at the Catholic school I attended for second and third grades just wanted me out, and they cared little if they had to break me to do it.

Dunno, this sounds somewhere on the spectrum between generalization and prejudice.

All the villains in the autobiography are white (not that all the whites in the narrative are villains). The one problematic black character is his father, Olayinka. In several places Jawando courageously provides the background for his difficult relationship with Olayinka (p. 123–124):

But Dad’s shame all too often cut him off from the healing power of fellowship. My mother’s agency and volition, that she initiated the divorce and that my father ultimately folded to her demands, embarrassed him. The fact that Uncle Tunde was a fellow Nigerian, I suspect, only amplified Dad’s humiliation despite any advice or kind words his cousin may have shared.

This is honesty and forgiveness, both solid Christian values.

In contrast, we do not hear the sides of the white villains in his story, nor are we given any extenuating explanations. The picture he gives of whites in general is as unfair as it is awful (p. 205):

If Hays [Kansas, where WJ’s parents met] was defined by the history of white supremacy’s murderous conquest over land and people, Long Branch suffered from yet another pathology of American life: the imperative to segregate.

Throughout the entire book, he refers to Blacks in initial capital, typically reserved for proper nouns, and refers to whites in lower case, typically reserved for common nouns. That is an intentional difference, and I wonder why he chose that convention.

Jawando isn’t the only person who falls into the anti-white narrative. Many whites do as well, certainly among the hateful progressives. Similarly, not all blacks anchor themselves in the anti-white narrative.

Regardless, I wonder why Jawando looks at today’s white population through an antebellum lens while at the same time playing basketball in the White House with President Obama.

Most importantly, I wish for Will Jawando the wisdom to treat everyone fairly regardless of race, and also to pursue policies that directly benefit (and do not injure) those with whom he so deeply identifies: young black boys.