In 1930, the Soviet newspaper Pravda published an article by Josef Stalin in which he summarized his accomplishments in agricultural policy:

The Soviet government’s successes in the sphere of the collective-farm movement are now being spoken of by everyone. Even our enemies are forced to admit that the successes are substantial. And they really are very great.

Two years later Stalin inflicted on Ukraine the Holodomor famine.

Stalin’s approach—denying failure, inventing success—will be my preferred mindset when writing my autobiography. I will leave out the incident in high school in which my BFF drove me to a party. When we arrived he said, “I shouldn’t have driven, I’m way too high.” Then he said, “I have a bag of hashish in the car.” Then a police cruiser drove by. Nope, I’d leave out all of that.

What I would include is the time I bought Bitcoin when it was at $25, bought 10,000 shares of Amazon at the same price, and advised Obama on his second presidential campaign.

In other words, my autobiography would be a farce.

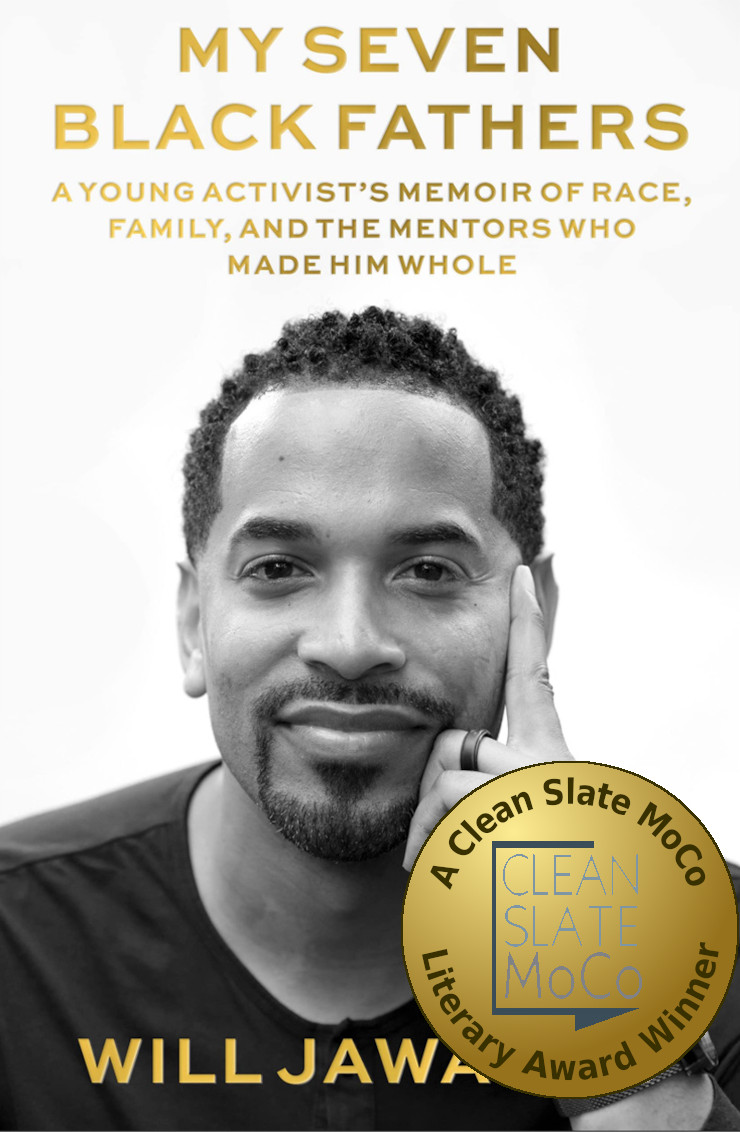

In contrast, in his autobiography My Seven Black Fathers, Will Jawando gives us an honest view into his childhood and early adulthood. Talking about his father (p. 16):

The truth is that Dad, like so many wounded men, embraced his defenses and rejected his vulnerability. This choice made him weak. It takes vulnerability to love.

Jawando shares with us his father’s vulnerabilities, and to a much greater extent his own. Love and anger, success and failure, respect and derision—he displays it all in a very candid way. He openly emphasizes his black identity, and subtly highlights his emotions.

The narrative is extremely well written. After reading all 228 pages, I am stills struck by the first paragraph in chapter 1 (p. 15):

There are many places to begin a story like mine, and they are often sites of grief or mourning. Without the stone memorials placed in the ground to commemorate these sites, Black men like me carry the heavy markers of absence in our memories. Suitcases and the echo of slammed doors. Someone you love turning their back on you and walking away, getting smaller and smaller until they disappear and a piece of you disappears with them.

We all carry the scars of absence, betrayal, fading pain, and pain that will never fade.

Which brings us to the one glaring flaw in Jawando’s autobiography. Talking about Jay Fletcher, one of the seven black fathers (p. 68–69):

Jay taught me that everyday life is an art, and with my thoughts and my words, I could write my own story. We call can.

This is false. Not all of us can. Not everyone can express their thoughts, not everyone can write their own story, neither in deeds nor in words. Jawando has the inner mettle and talent to do both.

The remaining installments of this series address Jawando’s background and how it impacts us, his constituents. It will be my assessment, and I apologize in advance for misreading or misunderstanding something he mentions, and I certainly do not want to cast any of the characters in Jawando’s book negatively. More importantly, my assessment isn’t important; if you want to understand Will Jawando, you need to read My Seven Black Fathers.